Irish Examiner "The Lisburn man is now one of the youngest ever senior international football managers..."

Author: Redmond Shannon, June 7, 2013

Johnny McKinstry was 15 when he crashed a motorbike and broke his collarbone. It was perhaps a sign – as if he needed it – that he would not follow in the footsteps of his father Billy. McKinstry Racing has been competing around Europe since before Johnny was born. Billy has been racing since the 1960s. The McKinstrys are a motorcycle family, but Johnny is an international football manager and that accident was just 12 years ago.

This weekend, Billy will be hoping for at least a podium at the Isle of Man TT. One of his riders, Ivan Linton, has qualified in second place for the Lightweight TT race on Friday. One day later, and 3,000 miles to the south, Johnny will be hoping to secure three points against Tunisia, keeping Sierra Leone in the hunt for a place at the 2014 World Cup.

“If I’m honest, this is where I wanted to go with my career,” says McKinstry. “Did I believe at some stage I would get the opportunity to coach a national team and go to a World Cup? It was always the ambition.”

The African sun has covered his face in Irish freckles since he first arrived over three years ago. He could pass for younger than his 27 years. The Lisburn man is now one of the youngest ever senior international football managers. André Villas-Boas may have been 21 when he coached the British Virgin Islands, but Sierra Leone is no speck on the football landscape. The country is similar in size and population to Ireland. Sierra Leoneans don’t talk about the weather, they talk about football – particularly the English Premier League. From August to May, the games pack-out football cinemas in towns and villages across the country.

However, the country’s obsession with the game has not been reflected with success for the national team. The Leone Stars, as they are nicknamed, have only played in two Africa Cups of Nations, and if McKinstry succeeds, he will be taking them to their very first World Cup.

His path to this job began around the time of his motorbike accident. He did some work experience with the Irish Football Association. McKinstry knew he didn’t have the skills of the other youngsters, but he also knew he loved football, and realised he could work on the other side of the orange cones. Pretty soon he was earning his first coaching badges.

“It was something to took to very naturally. By doing one or two things, in terms of tweaking performance and providing advice to players, I could see the impact it was having. From that stage onwards I always saw this as a career.”

Not everyone was so sure. “I remember meeting with career guidance counsellors at school and them asking what I wanted to be. My answer was always that I wanted to coach football for a living,” says McKinstry. “Now, I’ll not lie to you, the response was ‘Oh, well, you don’t just chose to be a football coach,’ and my answer was ‘why not?’ If you can chose to be a top lawyer or a top doctor then there’s no reason why you couldn’t end at the top of this industry.”

Looking back, he can understand the scepticism of his teachers. Just a decade ago, examples of successful career managers like Villas-Boas, José Mourinho and Rafael Benítez didn’t exist. Today, such ambition feels a little less unusual.

McKinstry worked on the coaching staff at Newcastle United and the New York Red Bulls, before taking a job as Academy Manager at the Craig Bellamy Foundation in Sierra Leone. “I was very comfortable and happy in New York, and my phrase at the time, in coming to West Africa, was ‘sometimes you’ve got to role the dice and hope it doesn’t come up snake-eyes.’ My mother didn’t like me for that saying at all. But my family have been very supportive and they are the reason I’ve been able to take such risks and achieve what I’ve been able to achieve.”

McKinstry’s older brother Darren has flown to Freetown for Saturday’s match against Tunisia. He will also accompany Johnny to Cape Verde for his second match a few days later.

Just two months ago, Johnny’s only concern was an energetic bunch of teenagers. The Craig Bellamy Foundation, set up by the Cardiff City striker, is Sierra Leone’s only football academy. Every year it recruits 16 youngsters, who reside at a campus near the capital Freetown. The foundation’s aim is not just to produce professional footballers, but leaders of the future. The boys receive an education following a U.K. curriculum. Scholarships are hugely prized in one of the world’s poorest countries – still largely recovering from the 1991-2002 civil war.

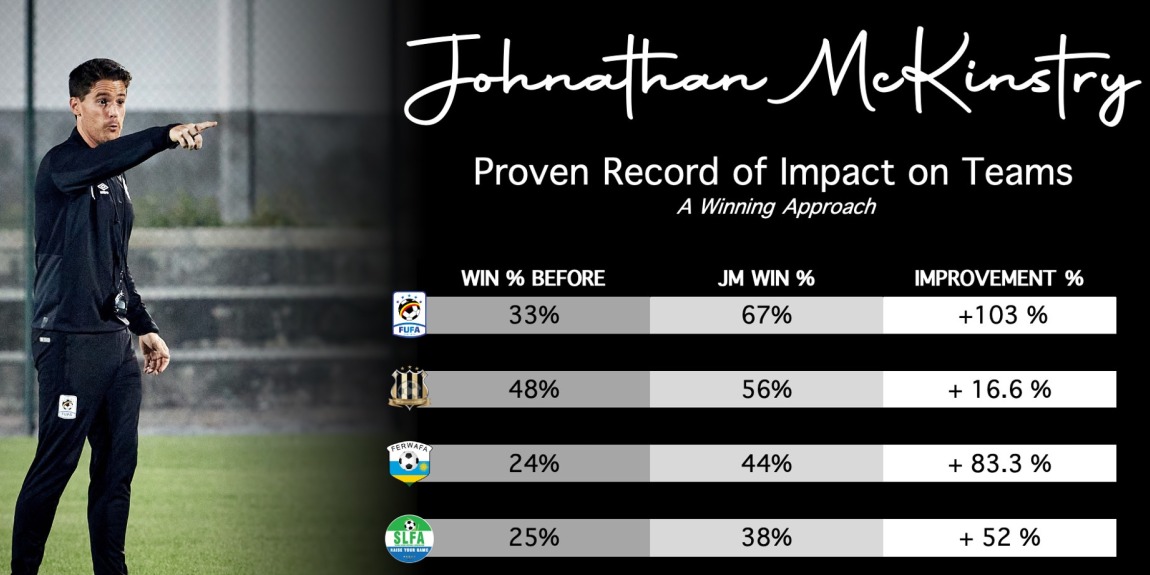

McKinstry has signed a three-game contract with the Ministry of Sport and the SLFA. He will delegate his coaching activities at the academy when dealing with the Leone Stars in June and September. The national team will need to win all three remaining group matches and hope Tunisia slip up again, just to get to the final round of African playoffs.

“I have been at every home international [since arriving in Sierra Leone], and have followed the away games on TV. My knowledge of the players has been quite extensive over that period,” says McKinstry. “I interact very well with everybody. I think it’s part of being from Ireland, we always get along with everyone we run into. It’s very easy for people to come to Africa and separate themselves from the local community, but I think you miss out so much when you do that.”

The previous coach, Lars-Olof Mattsson didn’t live in Sierra Leone. He flew in from Sweden just for games. “Having lived here for three-and-a-half years I have become very embedded in Sierra Leone society and almost feel like an honourary Sierra Leonean. I have gotten to know the country very well. So to have an impact on something the country is so passionate about is something I am very privileged and honoured to do.”

When Mattsson resigned in March he blamed poor organisation and communication issues with the SLFA and the Ministry of Sport. McKinstry says he hasn’t faced such problems, so far. Another major hurdle for the Northern Irishman is the absence of a domestic league. The Sierra Leone Premier League was due to start in March, but because of a lack of funds, it has yet to begin. Consequently, McKinstry has picked his squad from players who are based abroad, mainly in Europe.

Apart from knowing the local football scene, he says the greatest advantage to having lived here is knowing how things work.

“The speed at which things get done is probably the biggest challenge. Working in the U.K., Ireland and New York, you just pick up the phone and something gets done in five minutes. Here, that’s not the case. You have to have a lot of patience. That’s not to say you accept tardiness, or accept a lack of effort, but it’s understanding the restraints we are working within.”

It can be difficult for anyone who hasn’t been to Sierra Leone to understand those constraints. Many people here have two or three mobile phone numbers, because no network is reliable. The postal system is limited. Internet speeds are a fraction of those in the developed world. Most roads are not paved. Without a generator, electricity is intermittent, at best. The average Sierra Leonean lives on less than $2 a day, and is not expected to live past their 50th birthday.

Despite the challenges, McKinstry believes his players are good enough to give Sierra Leoneans something to be proud about on Saturday, and that his work, before and after his appointment, has helped to load the dice in favour of the green, white and blue.

“My ambition is, come the day that I step aside from this role, that the bar will have been raised, not just in terms of performance, but in terms of how everyone performs on a day-to-day basis,” he says. “Growing up, my father spent so many hours in the garage, working on the bikes, making sure they were tuned-up. You could see his commitment to excellence. Definitely that’s rubbed off on me in the amount of time and the amount of energy that I commit to football.”